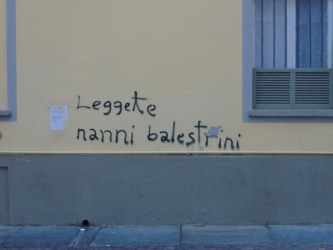

On a wall in a city in Italy is scrawled a graffito: ‘Leggete Nanni Balestrini’ – ‘Read Nanni Balestrini’. It brings you up short: an imprecation to read an avant-garde novelist is not something you often see written in spray-paint. Graffiti is all about staking an urgent claim to something unacknowledged, most often and most simply that you were there. Here, it is Read Nanni Balestrini. Why? Balestrini’s recently republished novel of Autonomia, The Unseen, gives some idea.

The Unseen is a novel determined by history. It was written and published ten years after the Years of Lead; as such it cannot end other than it does, in the brutalities of state repression and imprisonment. But it recovers, too, the exhilaration of the early years of Autonomia, and rejects sententious or easy moralising about the struggle. Such refusal of the simple position of literary pentito caused Balestrini no end of problems: many publishers rejected the novel for its violence, and its eventual publication by Bompiani occasioned a generalised wringing-of-hands across the Italian literary press over the novel’s failure to accord with the new consensus on Autonomia – that it was critically and ideologically impoverished, that it was the ineluctable progenitor of terrorism, that it was (above all else) out of harmony with the appropriate way of conducting politics.

Literary reactionaries abound, of course, especially among the ‘avant garde’, and though it’s easy to get the impression that the Autonomist period was freighted with dozens of intellectuals and writers involved with militant action, in fact there were always many more either explicitly opposed or serenely passive in the face of state brutality. But what is astonishing about the reception of Balestrini’s novel is the extent to which it was judged primarily on its non-literary dimension – i.e., in its positioning over the movement and move into armed struggle which constitute its raw materials. Its status as a literary object recedes in the face of its possible use as propaganda for either side; perversely, it is as literature rather than as document of the struggle that the novel is most important. For all that it may or may not serve as justification or provocation, The Unseen’s central questions are really those of survival and time: how human beings and human relationships survive or splinter in political struggle, how the puzzle of political history and individual human time fits together.

Balestrini’s background is in the literary avant-garde, which is to say that his writing is always conscious of the form in which it is cast. The Unseen is written in unpunctuated paragraphs interspersed with different voices, differing levels of narrative intervention, reading at times as a stream-of-consciousness recollection, stitched together across jumps in time. This is not literary pretension, but technique serving its object: in other words, it is the literary form taken to best embody the narrative – sensitive to the individual’s relation to history and politics, rendering its questions always in terms of individual suffering, immediate relationships rather than political abstractions. Its technique is then in service of the ethical-political axis that drives its story, in the achievements and suffering of its nameless narrator; this shift of the ethical axis away from the ragged contemporary consensus on the ‘responsibility’ of Autonomia for the repression undertaken by the Italian state and instead toward the individual political subject (replete with intense political bonds of friendship, love and solidarity) is perhaps what most outraged its early critics.

The story is a simple one: the unnamed narrator’s trajectory from working-class high-school rebellions, through squatted social centres, autonomist organising, the rancorous emergence of political violence and the experience of state repression and imprisonment. It bears the dedication ‘for Sergio’, the working-class Milanese autonomist whose conversations with Balestrini formed the prima materia for the novel. This fact, combined with the immediate style of the novel, makes it hard not to read it as a testimony. That is intentional, much of the novel’s power lies in it, but it remains a novel, not a transcript, and the question of its fidelity to specific historical events is less important than the story it draws out for the sympathetic reader. The narrative cuts between the history of the small affinity group (‘…that’s what we called it affinity group precisely because we were all in affinity about our way of living…’, p.104) and the narrator’s experience as a political prisoner, in prison revolts and their bloody suppression.

There are moments where any reader involved in extraparliamentary politics today will recognise eerie similarities with contemporary struggles, both in the attitude to police, and the ways in which differing political persuasions reassert themselves during struggle. For instance, during an occupation, members of a new Leninist political party arrive to bestow their sage advice:

they turned up with their party newspaper sticking out the pockets of their grey lodens they came up to Cotogno and me their leader got straight to the point what you need to do right away is call a mass meeting to discuss what’s to be done this spontaneous movement has to have political leadership first of all we’ll have a closed meeting between us and the occupation leaders to decide on the programme we’ll get the mass meeting to approve and so on finally they left none too happy but their leader threatened us all mass struggles are doomed if there’s no one to lead them you’ve got no political line and you’re dragging the masses to defeat and blablabla and blablabla

–p.41

The settling of scores with caricature Leninists aside, Balestrini’s novel reserves considerable ire for those on the hard left who collaborated with the Italian state, especially the communist parties and those party to the ‘historic compromise’, especially those who become gleeful persecutors of autonomists through roles in the courts. The anger at the PCI is palpable. But there is a more interesting point raised by this quotation, which is that it is one of the few moments in the novel where ‘politics’ as a recognisable field of discourse and activity – with ideologies, with parties, with bureaucrats – obtrude into the novel. This is not to cede that the novel is uninterested in politics – the entire novel is about one relationship to the political, which is everything existing – but that it breathes a total dissatisfaction with formal politics, viewing it as structurally corrupt and corrupting.

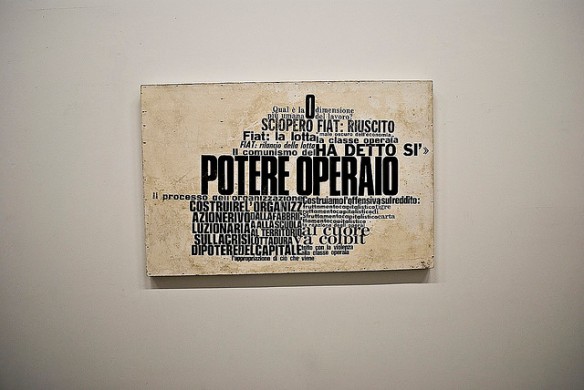

But this negating relationship to extant political institutions is not a total explanation for the submersion of political discourse in the novel. Early in the narrative, the protagonist reflects on a police raid on his family home resulting in the confiscation of his collection of literature and ephemera from the movement: for him this is not an indissoluble loss, because his political involvement has been located in the rage at his family’s grinding work life, the narrowness of subjugation it produces, in short the root of his involvement is not discursive. Balestrini’s choice of a largely uneducated working-class narrator is salutary: even other prisoners are surprised that he can’t read languages other than Italian, because they expect political prisoners to be teachers or professors. It is a reminder that the autonomist movement wasn’t a mass movement of Toni Negris or even Nanni Balestrinis, and arose in direct contest with material conditions. In other words, the political theory of autonomist writers is at best half the story – the struggle itself was instantiated in the attempt to live otherwise, in the practice of political struggle itself, and it is here that Balestrini’s eye is focused.

Reading this novel, it’s sometimes easy to forget that all of this is well within living memory. Any informed reader knows how the novel must turn out: the Italian state propounds a causal link between Autonomia and the armed struggle, interns, tortures and violently represses its activists. The novel must end in prison. As Balestrini knows this, he ejects the trappings of suspense, and instead intercuts the struggle within the prison, and its eventual defeat, with the prior struggle prior to imprisonment. Yet this is not a concession to the logic of the state: that the movement necessarily gives rise to clandestine armed insurgency, that it then necessitates imprisonment, instead we have the angel of history surveying the wreckage behind him, able to discern only in retrospect the bad decisions, the flaws, the mis-steps that spin wildly out of control. Solidarity is the ethical criterion of The Unseen, again and again it is counterposed to the bafflement of the police and judiciary, and it is the choice to keep silence in solidarity (and thus refuse to incriminate others by confirming the report of a pentito, and exculpate himself) that lands our narrator in prison. It is also the slow unravelling of solidarity by the grinding harshness of the prison regime that leads to the novel’s bleak conclusion.

The unravelling of solidarity and the grim destinies of the various members of the affinity group after solidarity evaporates constitute, to my mind, the novel’s substantive political intervention. Here, again, is why it outraged its critics: it leapfrogged the pointless afflatus of Italian parliamentary politics and the critics’ circle to deliver a message about survival to its readers. Survival, or the failure to survive, becomes the key question: how to survive in a way worth surviving? There are three key episodes here: one is the set-piece confrontation between the women and the men in the social centre, which leads to the women withdrawing from the project, the second is the argument that arises over the choice of some few members to enter the clandestine armed struggle, the third the emergence of heroin within the culture. All three are salient, and uncomfortably easily recognised as problems we still encounter. It would be too complex to explore each one in turn, but it’s worth quoting one of the women’s interventions in a meeting called to address problems in the occupied centre:

Valeriana starts speaking (…) we’ve had separate meetings we women on our own have talked about things among ourselves that’s how it started without being planned then it became something more serious it became a need to bring out everything we had inside us how we’ve lived in our relationships with you here in the collective and to make comparisons with the relationships we’ve had before well we’ve discovered that there’s no difference being comrades should mean being different from normality being better more advanced culturally and most of all in terms of human relationships but you’re not a single millimetre more advanced than other men in the relationships you have with women

–pp.150-151

This is not a complaint that should be news to much of the left, but all too often it is: that in the struggle we reproduce precisely those dynamics of power we seek to oppose. Balestrini’s narrator, despite doing the standard bristling that accompanies such complaints, realises in retrospect that ‘it was about a much bigger affair as we understood it later it was about a trauma a big trauma a big rupture maybe bigger than all the other things we were doing and that changed us all later’ – this is daring. Instead of locating simply in state repression the seeds of the movement’s collapse, the protagonist points to the flaws in the movement that burst open under the force of that repression.

How to survive in a way that’s worth surviving? The novel refuses to greet the assertion that the only possible conclusion of Autonomia was the armed struggle: in prison, the narrator finds himself not quite able to understand the younger prisoners, interned after the collapse of the movement into violent clandestine insurrection. This split is dramatised in a meeting where arguments go back and forth over the clandestine struggle, its abandonment of mass consciousness, wherein Scilla, always inclined to violence, points a revolver at the head of one of his comrades in disagreement. Something breaks. The emergence of political violence as vanguardism, as an attempt to direct mass consciousness through a series of bloody signposts, the ‘leap into clandestinity … to abandon a movement of thousands of people in struggle for a war waged by twenty or thirty’ causes the affinity group to split. Those remaining attempt to set up a pirate radio station, but find something has gone, that they are working more and more furiously to cover over a gaping wound.

Escape is the dream of many in the prison.Towards the end of the novel we hear of the eventual fates of many in the group. One ravaged by heroin addiction and in debt, one dealing it, one dead at the hands of carabinieri, one driven mad by prison and eventually a suicide. China, the narrators lover, vanishes. The last time she visits him in prison, the intercom is broken, and the two cannot hear each other. He notices her dress, she is, for the first time, wearing neat earrings and a wristwatch, who never before wore a wristwatch. How to survive? In this case by subsuming oneself again into capitalist society, extinguishing all dissent, bound again to the regulatory time of the working day. She is never heard from again. The conclusion of the novel is seemingly bleak: a burning brand held out of the bars of a prison, but censured by its isolation in the countryside, no one to witness the silent protest, all the bonds of solidarity unravelled and gone. It is a bleak conclusion, with a plane passing overhead, unable to see – or if it can see, unable to interpret – the last, feeble protest going on inside the prison below.

But it is not all. We have the novel. In his diaries from his time in prison, published at the same time as The Unseen, Antonio Negri cites Kundera’s fear that ‘our prison records will be the only things left of us.’ They are not. What is hopeful is not the conclusion of Balestrini’s novel, but the existence of the novel itself. Its protagonists have not been reduced simply to their records, but come to us in a living and pungent voice. It is unstintingly real, and poses devastating questions, questions which are ever more important to answer today: how to survive in a way that’s worth surviving? It is worth reading Negri’s Diary of an Escape in counterpoint with Balestrini’s novel. Negri’s picture is more hopeful – perhaps, indeed, because Negri effected an escape, and had numerous advantages that Balestrini’s narrator did not – and worth thinking on:

I am a Marxist. And I remain a Marxist. I ask myself, recalling prison, what it was, if not my trust in revolution, that gave me the strength to carry on working. A re-reading of that strong theoretical hope, of the optimism of the intellect which is Marx. Marx beyond Marx. Spinoza and the logical certitude of possible revolution. And the calm passion of this vision, which went right through the experience of prison. Lessen the anger against injustice by means of the analysis of its structural causes, and through this build a higher level of hate against exploitation and domination. Many people tell me that, like Marx, I too am a corpse – but I don’t see humour in their eyes, only fear. The advantage of my hatred is that it is articulated on, and mediated by, hope. … Marxism: it is the only practice that turns theory into a weapon.

— Antonio Negri, Diary of an Escape (London: Polity Press, 2010), Fol. 79, pp.148-9

So this is Balestrini’s question, that he throws out to us, the ethics of survival, or, another question, how to live and continue living without extinguishing ourselves? Negri again: ‘There is a revolutionary society that lives within this shit of developed capitalism.’ How to sustain it? So, yes, we need to ask these hard questions, we need to start to figure out how to answer them – read Nanni Balestrini.

Pingback: The Oxonian Review » Weekly Round-up

Pingback: On Nanni Balestrini

Pingback: On Nanni Balestrini « Random Information